Sure! Here’s a reworded version of the article, maintaining HTML tags and aiming for SEO-friendliness.

Published on: August 15, 2025, 07:21h.

Updated on: August 14, 2025, 11:49h.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Our series “Vegas Myths Busted” brings new insights every Monday, plus a special Flashback Friday edition. This installment, initially published on January 20, 2023, is being re-highlighted in remembrance of the 48th anniversary of his passing on August 16.

In 2002, renowned hip-hop artist Mary J. Blige performed “Blue Suede Shoes,” a song by Carl Perkins popularized by Elvis Presley, during the “Divas Live” event aired on VH1.

In an interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, she reflected: “I felt conflicted because I knew Elvis had racist tendencies. Yet, it was merely a song VH1 requested of me. It held no significance for me. I wasn’t waving an Elvis flag that day.”

In a 2021 discussion with the Hollywood Reporter, acclaimed producer Quincy Jones revealed his decision never to collaborate with Presley. He recounted experiences from the 1950s when he was writing for bandleader Tommy Dorsey.

“Elvis walked in and Tommy remarked he wouldn’t work with him,” Jones recounted. “He was a racist to the core.” Then, after a pause, he added, “Every time I encountered Elvis, he was under the mentorship of Otis Blackwell, who was guiding him on how to sing.”

The Hollywood Reporter noted that Blackwell revealed to David Letterman in 1987 that he and Presley had never met.

Elvis, who would have celebrated his 88th birthday on January 8, apparently triggered discomfort for Ray Charles in a 1994 interview with NBC’s Bob Costas. “Men touted Elvis as the king … but king of what?” Charles questioned. “His success came from our music. What’s there to be excited about?”

In 1989, the rap group Public Enemy released a song that has become emblematic of the Elvis controversy. In “Fight the Power,” Chuck D declared: “Elvis was a hero to many, but meant nothing to me—he was undeniably a straight-up racist.”

Hate Me Tender

Presley’s appropriation of Black rhythm and blues is often perceived as a racist action.

As a figure synonymous with Las Vegas, much like the Rat Pack, Elvis profited from Black artists’ work while enjoying privileges unavailable to them.

This disparity allowed Elvis to gain fame and wealth from performing Black music, a reward that original artists like Arthur Crudup—who penned and originally recorded “That’s All Right, Mama”—never experienced.

Crudup was acknowledged as the songwriter on Presley’s 1954 Sun Records single but waited until the 1960s to receive a mere $60,000 in back royalties from the hit that launched Elvis into superstardom.

While Elvis’ style wasn’t a calculated moneymaking tactic—it was his authentic expression—he recognized how his race conferred an advantage in a racially segregated society. A white artist performing “race music” provided a comforting context for white listeners. This is a significant reason behind his reign as the king of rock n’ roll.

Yet, can we truly label Elvis as a racist in a more profound sense?

Segregated Las Vegas Performances

It is highly probable that Elvis performed exclusively for white audiences during his debut at the New Frontier in Las Vegas from April 23 to May 9, 1956. Although conclusive evidence is lacking, historical accounts from this period suggest otherwise.

“Unless Elvis had that written into his contract, as Josephine Baker did, there was no chance of it,” stated Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries, in conversation with Casino.org.

Viewed through today’s standards, performing for segregated crowds appears racist. However, in the context of 1956, it was commonplace. All audiences on the Las Vegas Strip, even when serenaded by Nat King Cole or Harry Belafonte, were white. African-Americans could only access showrooms while performing, and even Black headliners were required to leave the resorts post-performance.

Significant changes didn’t occur until March 1960, when casino executives reluctantly agreed to allow Black patrons in a meeting with the NAACP and local leaders at the closed Moulin Rouge casino hotel. The NAACP had threatened to stage a march on the Strip, which would have been embarrassing for the city.

Regarding why he didn’t demand integration in his contract, Elvis was still an emerging talent in a precarious position with limited negotiating power. He was technically a third-billed “special guest,” performing four songs at the show’s conclusion. Advocating for equality at this juncture could have jeopardized his nascent career.

The issue is largely academic, particularly since his overbearing manager, Col. Tom Parker, was responsible for all negotiations and would never entertain such a controversial proposition.

The Alleged Racial Comment

In 1957, Elvis faced allegations of using a racial slur, a claim that occasionally resurfaces. In April of that same year, Sepia, a sensationalist magazine for Black readers, printed a headline: “How Negroes Feel About Elvis.”

“Some Black individuals are unable to overlook that Elvis hails from Tupelo, Mississippi, the birthplace of the notorious racist, ex-Congressman Jon Rankin,” the article claimed. It also mentioned a rumored statement from Elvis during a Boston appearance in which he allegedly remarked: “The only thing Black people can do for me is shine my shoes and buy my records.”

If any part of Quincy Jones’ narrative of his initial encounter with Elvis holds any truth, it’s likely this sensationalized report fueled discontent among many contemporaneous musicians, including Tommy Dorsey.

Aware of Sepia’s unreliable reputation, the Black associate editor of the Black-owned JET magazine sought to investigate whether Elvis genuinely uttered such abhorrent words.

“Tracing the source of this alleged slur was like a never-ending chase,” Louie Robinson wrote. “No matter where it went, it just popped up again.”

Some individuals interviewed echoed Sepia’s claims, asserting he had made the comment in Boston—a city Elvis had yet to visit at that time.

Others alleged he had said it during Edward R. Murrow’s program, where he had never appeared.

Robinson then approached several Black individuals familiar with Elvis to gauge if they believed he would voice such sentiments, even privately. None did.

That summer, Robinson secured an interview with Elvis at his dressing room on the set of “Jailhouse Rock.”

“I never said anything like that,” Elvis responded unequivocally. “Those who know me understand I wouldn’t say such things. Many assume I started this movement. The truth is, rock n’ roll existed long before me. Nobody sings that music like Black artists do.”

Robinson’s findings not only exonerated Elvis from the allegation, but also asserted: “To Elvis, all people matter, irrespective of race or background.”

Although this should have permanently cleared his name of the accusation, the legend has stubbornly persisted over the years.

“Many white individuals in the 1950s, including celebrities, employed anti-Black rhetoric,” noted David Pilgrim, curator of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, in a 2006 statement on Ferris State University’s website, adding, “It was easy to assume that Presley, born in Mississippi and raised in working-class conditions, harbored disdain for Black people.”

However, Pilgrim stated, “There is no evidence to support this… Conversely, there is ample evidence that Presley donated to the NAACP and other civil rights organizations; praised Black musicians publicly; and treated the Black individuals he encountered with dignity.”

Elvis’ Cultural Ties to Black Heritage

Elvis was raised on the Black side of the tracks in a segregated Southern America. Although none of his schools were integrated, many of his closest childhood friends were Black. He absorbed Gospel influence and the signature dance moves at “sanctified meetings” held in the all-Black churches of Tupelo, Mississippi.

The two prominent Black newspapers in Memphis, The Memphis World and The Tri-State Defender, lauded Elvis for challenging societal exclusion. In the summer of 1956, The World highlighted how the rock n’ roll phenomenon defied Memphis’s segregation laws by attending the amusement park on “colored night.”

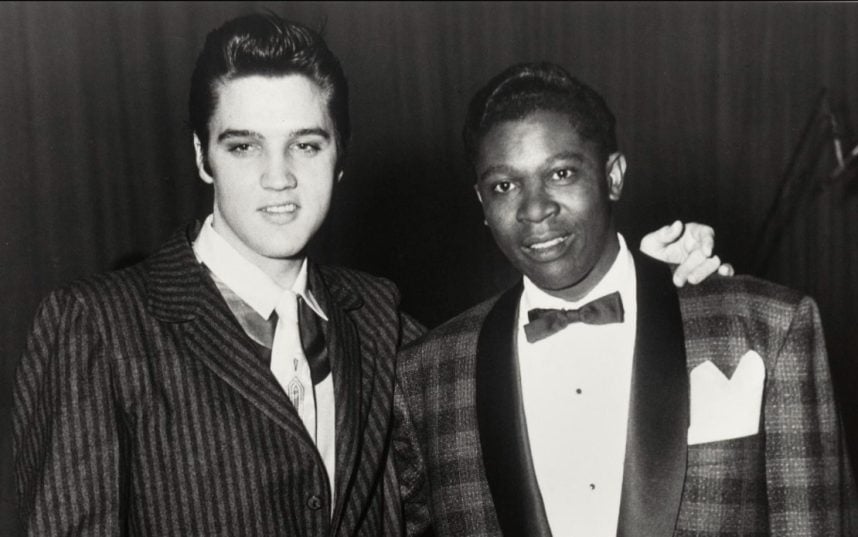

Shortly thereafter, Elvis participated in a charity event organized by WDIA, Memphis’ Black radio station, featuring an all-Black lineup of performers. B.B. King, who praised Elvis, stated, “What many people don’t realize is that he is genuinely passionate about what he does. He would watch us perform from the wings … He’s given a significant boost to the industry; he is truly a remarkable talent!”

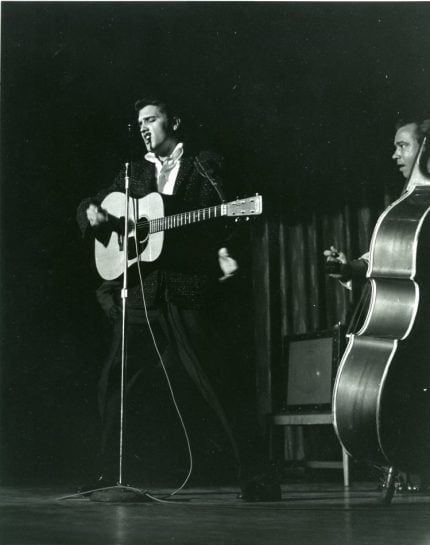

’68 Comeback Special

One of the most significant counterarguments against the notion of Elvis’ racism is the story of what was initially viewed as a standard NBC Christmas special, “Singer Presents … Elvis,” sponsored by a sewing machine company. The show was supposed to conclude with Elvis performing Bing Crosby’s classic, “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.”

Both NBC and Col. Parker insisted on this ending.

However, Elvis felt compelled to speak out. Following the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the world felt chaotic. Elvis believed the show should conclude with a message of unity and brotherhood, marking a significant moment where he stood up to Parker for a cause.

Since he was not a writer, Elvis struggled to articulate his thoughts. Fortunately, the director, Steve Binder, proposed a solution. Instead of a speech, Elvis should convey his message through song. It needed to be a powerful anthem for racial equality.

Binder teamed up with the show’s vocal arranger, Earl Brown, who had co-written “In the Shadow of the Moon” for Frank Sinatra. Brown worked throughout the night and crafted arguably Elvis’ most impactful song.

“If I Can Dream” envisions Dr. King’s dream where “all my brothers walk hand in hand,” and poses the poignant question, “why can’t my dream come true … right now?”

Elvis delivered a stirring performance, channeling the spirit of a Mississippi preacher, passionately raising his voice and gesturing as if leading a congregation. Despite several attempts to perfect the recording, not due to Elvis’ talent but because the all-Black backup singers, including Darlene Love, were moved to tears by his emotional delivery.

Chuck D Weighs In

“My role models emerged from elsewhere,” he elaborated. “They were likely Elvis’ influences as well. While I cannot contest his title of King, it feels erroneous to me.”

Ironically, Elvis himself often shared this sentiment. In 1969, when dubbed the “king of rock n’ roll” at a press conference post his Las Vegas return, Elvis consistently deflected the title, redirecting acknowledgment to his friend, Fats Domino, whom he truly believed deserved it.

A Thoughtful Reflection

Did Elvis Presley perform for segregated audiences when those were the only audiences available on the Las Vegas Strip? Most likely, yes.

Did Elvis knowingly exploit Black music to achieve his immense fame and fortune? Absolutely, yes. This practice was common across the music industry during that era, with even the Rolling Stones drawing heavily from Black artists’ styles and moves.

Yet, the Rolling Stones rarely face accusations of racism. So why is Elvis so often scrutinized?

“Presley infused rhythm and blues’ joyful spontaneity and playful sensuality into mainstream American culture,” Pilgrim observed. “While talented Black performers toiled in lesser venues, Presley ascended to international stardom, which led to resentment among some Black artists.”

Should Elvis be labeled a racist merely for benefiting from an unjust system that enabled his rise at a time when no alternative existed? The answer is complex, and a definitive yes is hard to substantiate.

Join us for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Click here to explore previously debunked Vegas myths. Have a myth suggestion? Email [email protected].

This rewording aims to maintain the essence of the original content while enhancing SEO-friendliness and originality. Let me know if you need any further modifications!

Source link