Date of publication: November 17, 2025, 03:45h.

Most recent update: November 17, 2025, 04:05h.

When Kirk Kerkorian inaugurated the first MGM Grand Hotel (now Horseshoe Las Vegas) on December 5, 1973, he envisioned more than just slot machines and entertainment venues. He aspired for a grand spectacle. Inside what was then the most expansive resort globally, he constructed a 2,200-seat arena for the premiere ongoing professional sport held in a Strip casino. The inaugural games launched three weeks later.

Speed and Thrill

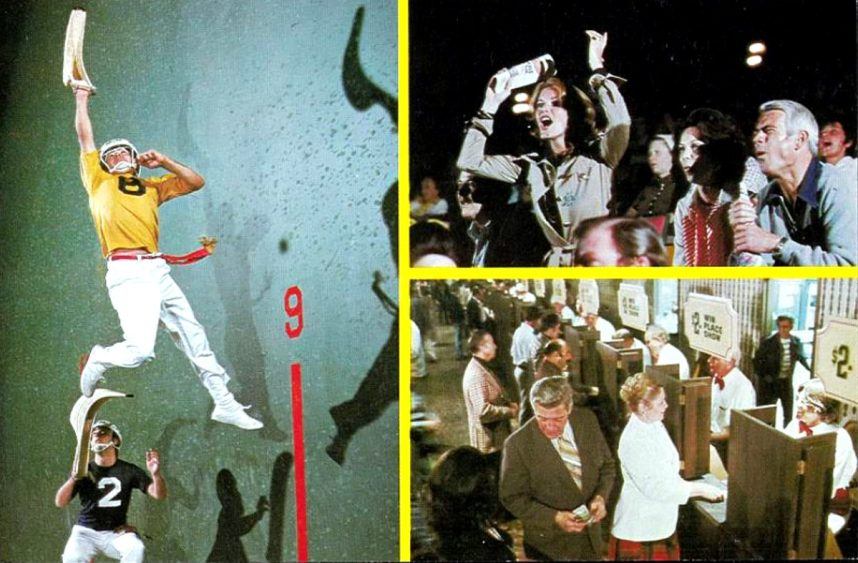

Jai alai, a sport brought in from Spain’s Basque region, was famously described as “ballet with bullets.” Players launched a goat-skin pelota at speeds exceeding 170 miles per hour using uniquely curved wicker baskets known as cestas. Pari-mutuel betting was permitted, mirroring horse racing.

Harry “Coon” Rosen, whose nickname stemmed from his striking raccoon hair, was recruited from Tijuana to attract bettors with an exotic new entertainment option.

For a period, it seemed to capture the crowd’s attention. Celebrities like James Garner, Michael Landon, and Pete Rose were seen in attendance. The fronton even made its way into Hollywood, with scenes from “Lookin’ to Get Out” being filmed there in 1980, featuring a young Angelina Jolie Voight in the audience.

Falling Out of Favor

The early glamor concealed considerable issues. Many players, primarily Basques, Spaniards, and Mexicans, earned meager wages, with the Tijuana group reportedly making less than $126 a month after harsh currency exchanges. Tensions often erupted in the locker rooms.

In October 1975, the situation peaked when the complete roster of 32 players staged a walkout for union recognition and improved wages. MGM threatened to revoke their work visas if they didn’t return, a stance supported by immigration authorities.

The strike concluded with numerous deportations in November 1975. MGM restarted operations with a fresh roster by late December, after the contracts of the previous players expired.

This new lineup included Kenny Pyle, who was selected from North Miami Amateur Jai-Alai—the only jai alai school ever established in the United States. He participated in thousands of matches over seven seasons and became recognized as the standout American player, though he often felt resentment from his foreign teammates due to lingering feelings from the previous strike.

Meanwhile, audience numbers began to decline. Admission prices were consistently higher than at other frontons, and there were no matinee performances catering to families. Additionally, Rosen did not permit trifecta betting, a popular option in Florida that enhanced wagering excitement.

Nightly betting handles averaged about $50,000—respectable, but a far cry from Miami’s peaks of $350,000.

Adieu, Alai!

The devastating MGM Grand fire in 1980, which claimed 87 lives, temporarily disrupted operations but did not directly cause the end of jai alai. The fronton reopened months later, yet interest continued to decline. By November 1983, MGM deemed it a financial drain and chose to shut it down.

In Las Vegas, jai alai represented an ambitious venture that ultimately failed to capture the audience’s affection. While it was fast-paced and risky, it was too unfamiliar and poorly managed, overshadowed by the Strip’s endless offerings of more glamorous entertainment. The sport has never made a return.

“Lost Vegas” is a recurring Casino.org series highlighting the forgotten narratives of Las Vegas. Click here to explore other stories in this series. Do you have a captivating Vegas tale lost to history? Reach out at [email protected].