Published on: October 21, 2024, 03:00h.

Last updated on: October 21, 2024, 12:53h.

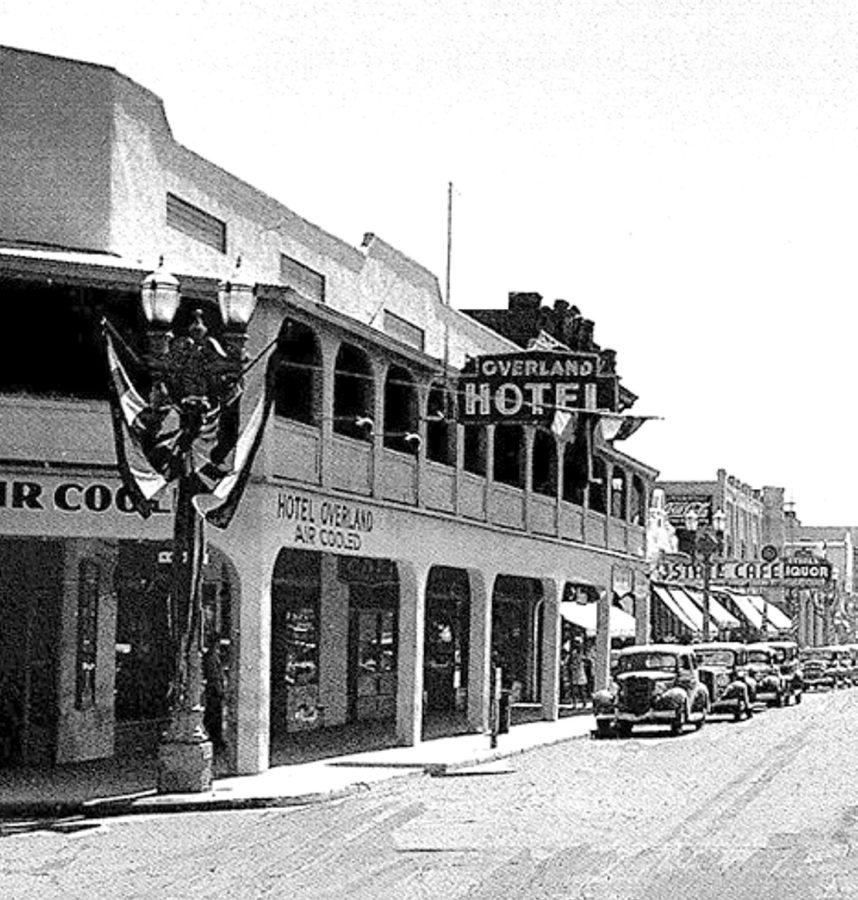

Even the 2,300 residents of Las Vegas at the time realized that the small tombstone shape announcing the name of Fremont Street’s Overland Hotel was special. And that feeling was confirmed when the Las Vegas Evening Review dedicated a story to it.

“The Overland Hotel is displaying a new neon gas-electric sign, of the most modern design, adding considerably to the appearance of that section of the city,” the newspaper announced on Sept. 28, 1928, 10 months before it merged with the Clark County Journal to become the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Of course, no one had any way of knowing how special it was — that this 2-by-5-foot electrified sign represented the very first use of the inert gas in the city that would one day become synonymous with it.

That’s why, when the Overland Hotel replaced its neon sign with a bigger one three years later — something it would also do seven years after that, owing to the blinding neon competition — no one bothered saving the original sign.

Why would anyone save a bird-poop encrusted sign when the new one was so much better?

But that original sign was the first shot fired in a war of one-upsmanship among hotels and restaurants that, a decade later, would result in the branding of Las Vegas as “the city of neon,” its third most famous nickname after “Sin City” and “Lost Wages.” (OK, so it was a distant third.)

Had anyone saved the sign, it would no doubt be the centerpiece of the Neon Museum today. (The Neon Museum did not get back to us with a comment in time, but trust us, it’s true.)

The Overlooked Hotel

The first neon sign wasn’t the only claim to history that can be made by the Overland. The property at 2 Fremont St., was sold during the 1905 railroad auction for $1,750 ($62,600 today) to John P. Wisner, who opened the hotel on it a year later.

After Wisner died in 1922, the hotel was inherited by his daughter, Ethel Wisner Genther, making her the city’s very first female hotel owner. And it was Genther who can be credited with the decision to install Las Vegas’ first neon sign six years later.

Another reason the Overland made history is a bad one. It burned to the ground on May 23, 1911. The worst hotel fire in Las Vegas to that point began in a first-floor restaurant. One person died and several more were injured after jumping from the second-floor balcony.

The volunteer Las Vegas fire department, with its two hoses and a hand cart, could do little more than watch the hotel burn. The tragedy was one of the main reasons Las Vegas decided to incorporate a year later. (One of the benefits of incorporating was a modern fire department.)

Wisner rebuilt his Overland in the same spot — bigger, better and with less wood. (The Las Vegas Age’s Nov. 18, 1911 front-page headline called it a “Handsome New Concrete Hotel.”)

It was so modern, it even boasted a “big free sample room” where traveling salesmen could display their wares.

In 1949, J. Kell Houssels Sr. decided to move his Las Vegas Club casino — which in 1930 installed the second neon sign on Fremont Street — next door to the Overland across the street. The Las Vegas Club expanded to take up most of the Overland’s first floor — except for the street-facing Talk of the Town bar which, in 1952, became the Chatterbox.

In 1962, Jackie Gaughan and his partners, Mel Exber and Larry Hezelwood, bought the Overland and Las Vegas Club for $1 million. They gradually phased out the Overland brand over the next several years, as the whole shebang became the Las Vegas Club casino hotel.

The 1911 Overland building was converted entirely into casino space and given the exterior façade of a baseball stadium in 1980, when the Las Vegas Club built a 224-room hotel tower behind it.

Both structures were demolished in 2015 to build today’s Circa Resort & Casino.

“Lost Vegas” is an occasional Casino.org series spotlighting Las Vegas’ forgotten history. Click here to read other entries in the series. Think you know a good Vegas story lost to history? Email [email protected].